Hey, it’s Charles.

So the book came out and the world reacted pretty much exactly how I expected.

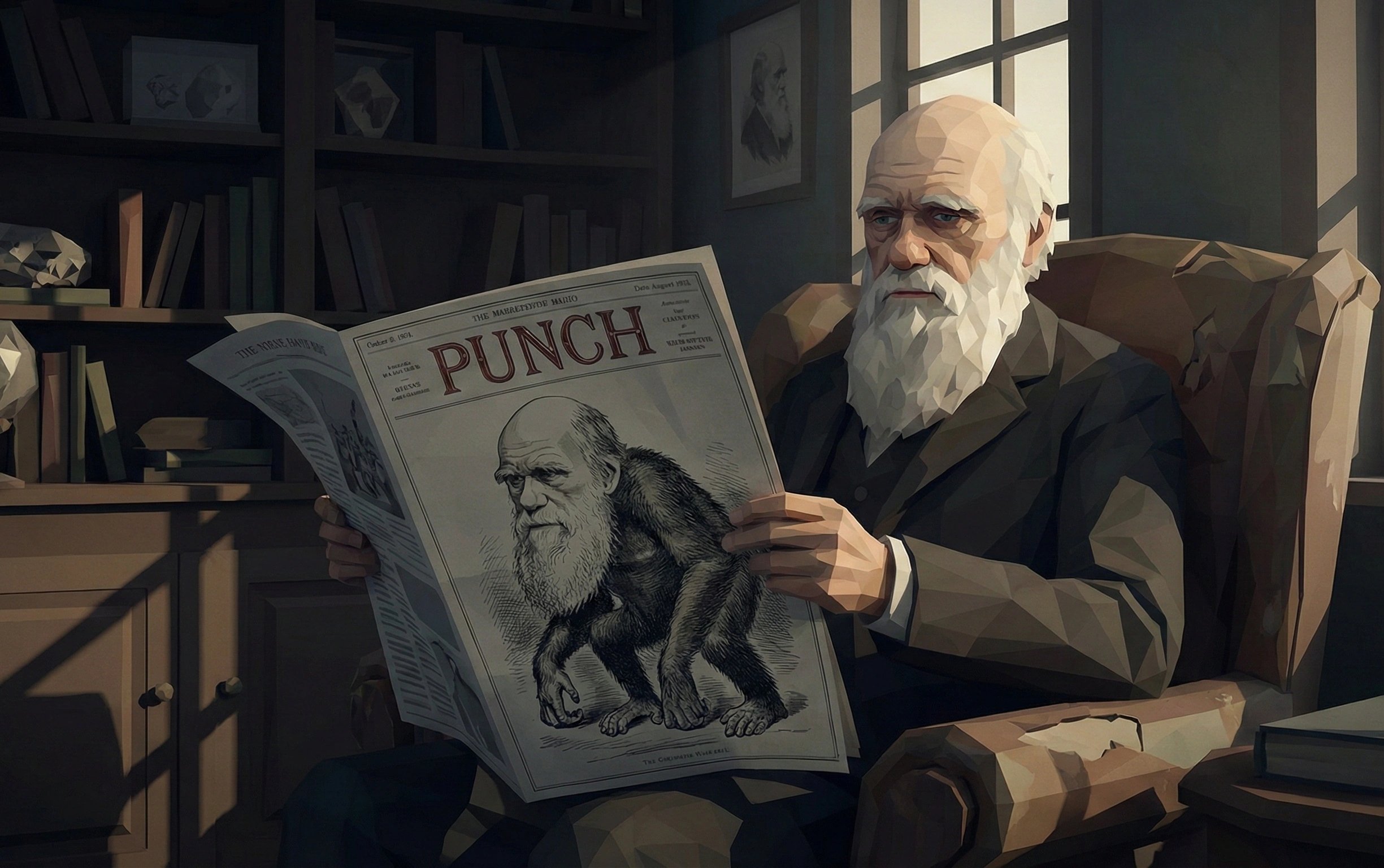

The Church is furious. Newspapers are printing cartoons of me with the body of a monkey. Clergymen are giving sermons about how I am an agent of moral decay. A bishop named Samuel Wilberforce — who has definitely not read the book — has been telling anyone who will listen that my theory is an insult to God and human dignity. One reviewer wrote that I had tried to “dethrone mankind from its place in creation.” Another just called me dangerous.

I have read all of this from my house. Because I am not going anywhere near any of it.

I am not a fighter. My stomach cannot handle public debates. I wrote the book. The book can speak for itself.

But here is the part that still makes me laugh.

My friend Thomas Huxley read the book and immediately appointed himself as my personal defender. Nobody asked him to. He just decided. Huxley is everything I am not — loud, confrontational, absolutely delighted by a good fight. He once told me he was “sharpening his claws” in preparation for the debates. The man treats scientific arguments like boxing matches and he has been waiting his entire career for something worth swinging at.

The big moment came at Oxford. The British Association held a public debate and Bishop Wilberforce showed up ready to destroy my theory in front of a huge audience. He gave a long, theatrical speech and then turned to Huxley and asked — very smugly — whether it was through his grandfather or his grandmother that Huxley claimed descent from a monkey.

The room laughed. Wilberforce looked very pleased with himself.

Huxley stood up and said he would rather be descended from an ape than from a man who uses his intelligence and influence to introduce ridicule into a serious scientific discussion.

The room erupted. A woman fainted, which seems excessive but it was a different time. Wilberforce had no response. It was over.

I was not there. I was at home. I think I was looking at earthworms. Huxley wrote me a letter about it and I could practically feel him grinning through the paper.

The thing is — and this is what I want you to understand — the argument was never really about me. It was about whether people are brave enough to look at evidence and follow it wherever it leads, even if the destination is uncomfortable. I did not invent natural selection. I observed it. The finches did not change their beaks to suit my theory. The fossils did not arrange themselves to support my argument. I just looked carefully enough and honestly enough to describe what was already there.

That is all science is. Looking at what is actually in front of you instead of what you were told should be there.

It has been a few years since the book was published. The fury is dying down. Slowly, the scientific community is coming around. Not because I convinced them — because the evidence convinced them. The truth has a way of being patient like that.

I spend most of my days in my garden now. Studying earthworms. I know that sounds ridiculous after everything — the Beagle, the Galápagos, the theory that changed how humanity understands itself — and now I am lying on my stomach watching worms move through dirt. But earthworms are extraordinary. They process the entire topsoil of England through their bodies. They are quietly, invisibly reshaping the ground beneath our feet and nobody pays attention.

I like that. The most important work is often the work nobody notices.

My health is not great. It has never really been great since the Beagle. But I have my garden, I have Emma, I have my children, and I have a stack of earthworm observations I am unreasonably excited about. My father told me I would be a disgrace to the family. I think he would have come around eventually. Probably not about the earthworms though.

If you are someone who feels like you do not fit the path laid out for you — the degree you are supposed to get, the career you are supposed to want, the version of yourself other people expect — I want you to know I was that person too. I was a dropout and a beetle collector and a seasick mess on a tiny boat. And the thing that saved me was not talent or genius. It was the willingness to look at things carefully and ask questions even when the answers were frightening.

— Charles